Wonderful Scientist Wednesday

Bertha Parker Pallan

Bertha “Birdie” Parker Pallan Cody was reportedly born in a tent on an archaeological dig, August 30th 1907. From early on, Birdie was fated to be a talented archaeologist — although her accomplishments were not always recognized by the male-dominated field of study.

Birdie’s parents nurtured her development. Her father, Arthur C. Parker was born on the Cattaraugus Reservation of the Seneca Nation of New York to a schoolteacher mother. His father was only half Seneca, but his family had strong ties to the leaders of the Seneca people, including Ely S. Parker (Arthur’s great-uncle) who served as a general under Ulysses S. Grant and later as the first Commissioner of Indian Affairs. In 1903, just four years before Birdie was born, Arthur was made an honorary member of the Seneca tribe. Arthur is known for his work as the State Archaeologist for New York.

Birdie’s mother, Beulah Tahamont, grew up as a model, actress, and performer, however she was also one of the first students from a first nation tribe to attend public school in New York. Beulah was born as a member of the Abenacki Nation of Northern Maine and Canada. Her parents starred in many of the earliest silent films — working specifically with D.W. Griffith in works such as The Birth of A Nation. In a newspaper announcement of Beulah and Arthur’s wedding, Beulah is heralded as a highly intelligent woman.

Growing up, Birdie worked on archaeological digs with her father and mother. After their divorce, Birdie and her mother moved across the country to Los Angeles. There her mother remarried an actor and Birdie was hired by her uncle, another archaeologist to assist on digs in the desert.

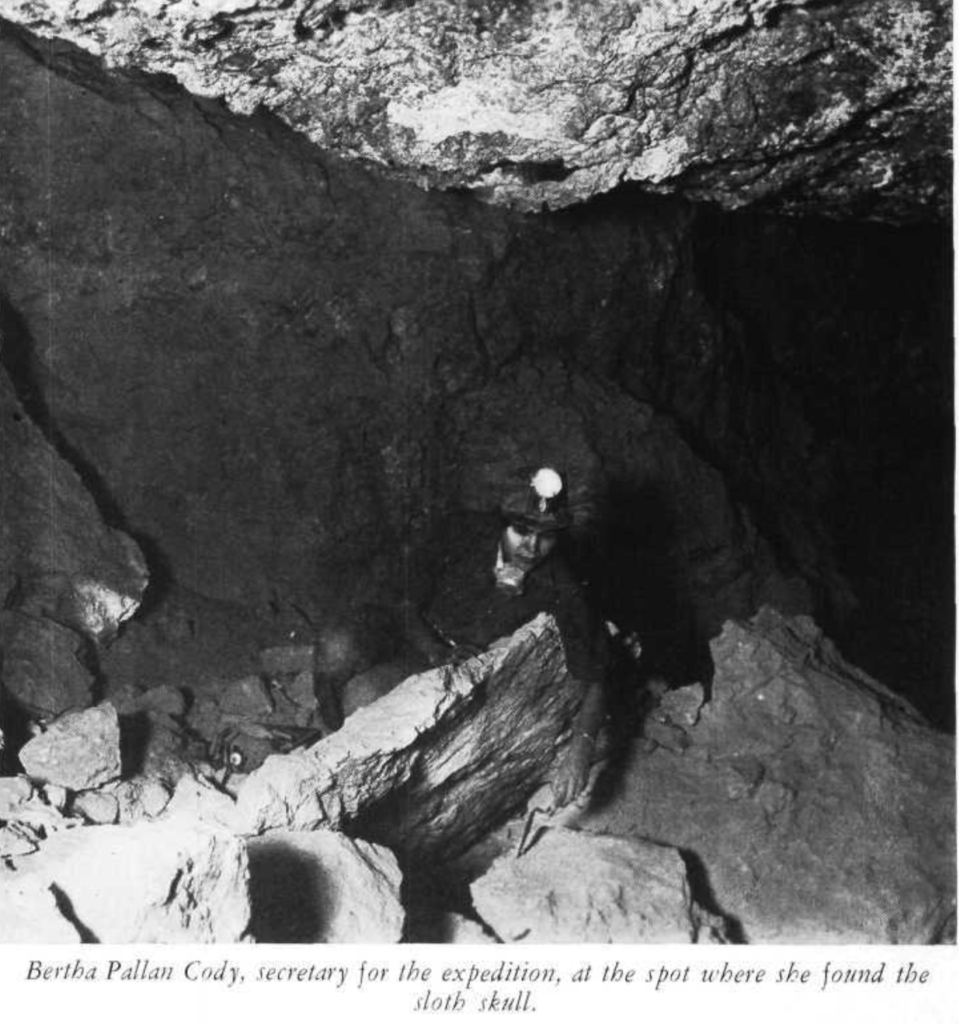

Although she had no formal training from college, Birdie went on to graduate from a field assistant and secretary to a notable archaeologist in her own right. After learning through apprenticeship with her uncle Mark Raymond Harrington at the Mesa House and other locations, Birdie went on to make discoveries. Although she was smaller than the men on the dig team, she was incredibly brave. While onsite at the Gypsum Cave in Nevada, Birdie squeezed into the deepest crevasse of the cave and discovered an extinct sloth skull. While the archaeologists were in the cave to study the remains of the earliest settlers of North America, Birdie’s discovery allowed the team to hire a paleontologist to study the early animal remains they found.

Throughout the course of her work, Birdie was often mentioned as the niece, daughter, or wife, instead of her working titles as archaeologist, ethnographer, and author. However, she continued to produce important work. Birdie went on to publish a number of papers and articles detailing subjects from basketry to Southwest Native American lore and she always made sure to record the names of her interviewees and subjects. She would go on to include some of these Native people as co-authors, a practice that is now frequently accepted among ethnographers, but in her time, was seen as totally novel.

Subscribe to stay in the loop with all our exciting activities!